|

HiddenMysteries.com HiddenMysteries.net HiddenMysteries.org |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

Secrets of the Lost Canyon

Wednesday, December 27 2006 @ 01:38 PM CST

Increase font Decrease font

This option not available all articles

When its existence was announced in the Summer of 2004, Range Creek Canyon triggered worldwide interest in a special parcel of land wedged in a remote corner of Utah.

Somehow, a Utah ranching family had defied the pressures of encroaching modern society and tourism. The Wilcox family had protected hundreds—if not thousands—of ancient sites of the now-vanished Fremont Indians. Despite the passing of five hundred years since the mysterious “disappearance” of the Fremonts, the sites and their artifacts had remained untouched. It was shaping up to be a wonderland for archaeologists.

But, behind the headlines and the media hype, there were other stories to be found. Stories that unveiled political deal making, competing interests forced into uneasy alliances and unspoken pressures that could shape the fate of Range Creek Canyon.

Through the groundbreaking documentary Secrets of the Lost Canyon, and this companion website, KUED invites you to step deeply into a very special place and confront its very challenging issues.

See video on this link:

http://www.archaeologychannel.org/content/video/lostcanyon_700kW.html

*******************************************

FREMONT PEOPLE OF UTAH

The Fremont People of Range Creek Canyon, Utah by Ellen Sue Turner

June 19, 1999, I accompanied Pierce, John, and Tom on a survey and data-gathering trip to Range Creek Canyon, Utah. Our flight from Love Field, Dallas, to Price, Utah was aboard a Merlin Fairchild turboprop plane. The flight was smooth, fast and comfortable. We cruised at 250 knots/hour at an altitude of 20,000 ft.

Waldo Wilcox met us at the Price airfield. Our destination was Wilcox’s ranch in Range Creek Canyon. We set off in one-ton, four-wheel drive Ford trucks. The last 40 miles of the 63 mile trip took us through Horse Canyon and Little Horse Canyon on a winding one-lane dirt road, over a pass at an elevation of 9,000 feet, and down to the ranch in Range Creek Canyon at an elevation of 5000 feet. The trip was slow and rough, and in wet or snowy weather, it can be extremely hazardous.

Wilcox’s grandfather was born in Wyoming and moved to a plot of land east of the Green River in 1883. When the government enlarged the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in 1941, the family moved to Range Creek Canyon. In 1951, Wilcox expanded the family holdings to 4200 acres, which include 20 miles of the 50-mile Range Creek Canyon. The ranch is surrounded by 100,000 acres of BLM wilderness land. Wilcox runs about 245 head of cattle on the land and keeps a dozen horses.

The cattle graze in the canyon for part of the year and after calving and branding, they are driven up the narrow dirt road to the grazing land that the family owns above the pass. Many lose their way or are lost in falls off the cliff—it takes skill, risk, and hard work to make the drive each year.

The land in the canyon is irrigated by five wells. Springs and trails are found on the faults and when Wilcox first drilled for a well, he hit water at five feet. He dug the well to 50 feet and reinforced the walls to prevent a cave in.

FREMONT CULTURE

The natural isolation of Range Creek Canyon has served to protect much of the archaeological evidence of the ancient ones, known as the Fremont people, who once inhabited this canyon. When these peoples appeared in eastern Utah is a moot point, but we know that they lived in many different kinds of settings and were able to adapt to all of them. I doubt that Fremont occupation in this area was ever too intensive – perhaps owing to the high elevation of the region and the consequent short growing season. However, exploiting the marshlands in the canyon, which are lacking on the Colorado Plateau, would be productive

There is evidence of indigenous development in the area since Archaic times but about A.D. 500, the old hunting and gathering bands gave way to a fairly large and relatively sedentary population in the areas where resources were readily available. Where resources were scarce, the Fremont people lived in small, highly mobile kin-based groups, exploiting the resources available. The key to understanding them is variation. Some were settled farmers growing crops of corn, squash and beans along snow-fed steams and mountain ranges, others were nomadic desert hunters and gatherers living on pinon nuts, bulrush seeds and mountain sheep. Still others would shift between these styles, perhaps living at all these sites within a lifetime. Bear, mountain lion, mountain sheep, rabbits, small rodents, lizards, snakes, raccoons, etc. and many kinds of marsh fowl and birds frequent Range Creek Canyon today. Common types of flora we observed were cottonwood, box elder, pinon, spruce, cedar, pine and aspen. choke cherries and sage were plentiful—after an unusually wet spring, the landscape was green and flourishing.

Many of the traits of their partly farming culture were similar to those of the Anasazi farmers to the south, but the Fremont culture is characteristically Utahn – they are identifiable as a distinct culture of small kin-based groups of people varying from sedentary populations in villages to highly mobile groups.. The Anasazi are best known for their complex social organizations, elaborate kivas, and road systems.

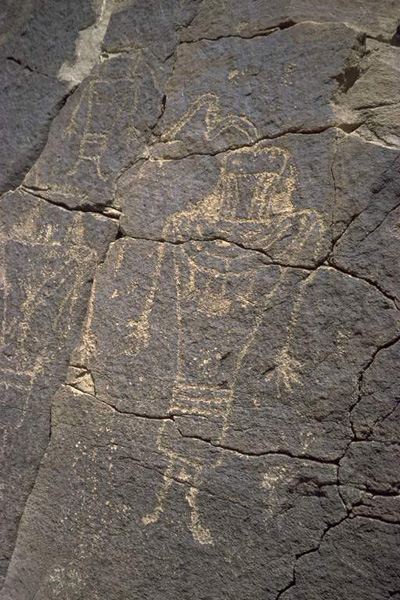

The most distinctive feature of the Fremont is their unique rock art style, typified by horned, trapezoidal-bodied anthropomorphs, found everywhere the Fremont people lived. In the strongest Fremont areas such as along the Fremont River, near Vernal, the figures are large and have necklaces, earrings, shields, swords, loin clothes and fancy headdresses. Headgear of feathers and deerskin occur in the archaeological record and pendants of sandstone, turquoise, bone, tooth and shell. Their feet point out to either side and the fingers are splayed. They also developed a stylized way of making spirals, concentric circles and circular motifs. Mountain sheep were very important and subsidiary designs such as snakes, centipedes, insects, animals, tracks and wavy lines and zigzags are typical. Hunting scenes with shamans or bowmen are also common. Pictographs are easier to execute than the carving/scratching technique of petroglyphs. For pigments they used natural colored clays, red and yellow ochre, and charcoal. Yucca fibers or animal hair made good brushes.

Many Fremont figurines, which are rare and unique, were made in human shapes and may have been used in ceremonial rites.. The Pilling figurines, one of the best examples we have of Fremont figurines, were discovered in 1950 by Clarence Pilling in a small side canyon of Range Creek Canyon and are now at the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum in Price, Utah. I saw them and all of the figurines are made of unbaked clay with applied clay ornaments and show remarkable skill and artistry. The figurines range in size from four to six inches, and still show evidence of red, buff and black paint. The rock overhang where they were found is typical of the many rockshelters, small caves and niches found within the canyon -- probably convenient for seasonal or intermittant use.

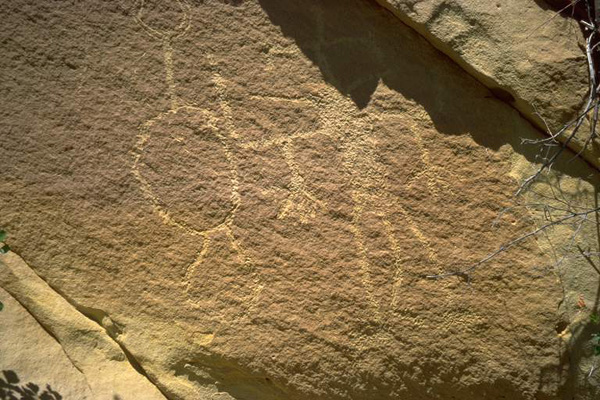

One such site, on an arched promontory high above the canyon, included two burials. A curious pictograph (22, 24) is similar to the arched promontory, has an anthropomorph in the middle and is located on a canyon wall with a view of the arch but of course we don’t know what the big "circle" is – the Wilcoxs call it "the television screen." The Fremont did do some painting of shields. This was very large for a shield and as far as I know landscape features do not appear commonly in rock art although it is often proposed that wavy lines are trails or rivers. If they do represent the landscape elements it’s really hard to prove that that is the case. Another rockshelter where two eroding burials are evident, is closely guarded by the Wilcox family.

The Wilcox family has surface-collected numerous artifacts over the past 50 years, which are unique artifacts of the Fremont culture. Shown here are examples of Fremont thin-walled gray pottery. This is probably the single most distinguishing non-perishable feature, which ties these people together. Plain gray wide-mouthed jars and narrow-necked jugs with strap handles like this basalt-tempered Sevier gray pot shown here, are common utilitarian forms at Fremont sites. Actually, five different pottery types have been defined on the basis of differences in temper but it appears that many local wares were also produced. The early potters used a coil and scrape technique in their construction with limestone as a temper. Variations in temper and the granular rock or sand added to wet clay to insure even drying and to prevent cracking are what distinguish Fremont pottery from other types. Examples include Ivie Creek black on-white and Snake Valley and Sevier black on gray varieties with geometric design elements similar to those used by Anasazi and other Southwestern groups. The broken pot in figure 89 and shards of many of these varieties of Fremont pottery are found in the Wilcox collection. The fingernail impressions along the rim of the neck are a common decorative technique found in late Prehistoric pottery. Madsen (1989:48) suggests this as one of the few bits of material evidence supporting a connection between The Fremont and later peoples of the area.

Characteristic Fremont metates with small secondary grinding surfaces (thought by some to have been used in conjunction with stone balls found at sites – and thought by others to show a connection to the Mogollon who have similar metates) are commonly found in the canyon in association with the remains of shallow, circular pithouses which, probably, had above ground rock, pole and mud, or brush-hut wind breaks. Winters in the Great Basin can be long and cold. In the 60 years that Wilcox has lived in the canyon, the coldest winter reached 30 below zero.

Remains of collapsed pit houses in small, probably extended family settlements, are found throughout the canyon near the marsh and pond and springs and on terraces up the canyon walls. Some are on rock ledges on hill slopes above the creek flood plain. The ones I saw were always on elevated ground – one was on an elevated rock formation in the middle of the meadow .

Small stick and mud-walled granaries are common in crevices and overhangs high in the walls of the canyon – they are difficult to reach or see by the casual observer. They were probably used to cache seed corn and other resources during periods when valley sites were abandoned. One intact granary from Range Creek Canyon is in the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum in Price. Tiny corn cobs and beans were also found in the collection.

Fremont moccasins are another unique trait. They are very different from the woven yucca sandles of the Anasazi. Some were constructed from the hock of a bison which was accomplished by girdling the leg at two points and then removing the hide as a skin tube. Or, from hide taken in pieces off the forelegs of deer or mountain sheep leg. An interesting addition was dew claws, sewn on the heel portion of the sole as hobnails. The moccasin shown here has a tuff of hair on it. Slide 86 shows a fragment of matting made from cattail or bulrush, which may have been used as a sleeping mat and a tiny example of their classic one rod and bundle basketry – another unique construction style, which was markedly different from the Anasazi or later Ute, Paiute and Shoshone.

Other artifacts found in the Wilcox collection include a wide array of bone needles and stone awls (to use as punches, and in weaving and engraving,), bone and shell beads, arrow points, knives, scrapers and other stone tools made from an interesting variety of cherts, obsidian, pink agate, and what looked like alibate from the Llano Estacado in Texas. One large tool was knapped from sandstone. Elongated corner-notched and small side-notched points are characteristic but too few, too varied and too limited in distribution to make them a distinguishing trait.

ROCK ART

Examples of pictographs and petroglyphs from the walls of Range Creek Canyon follow:

The figure in slide 80 is a little different and looks more like Barrier Canyon style.( found in western tributaries of the Green River in eastern and central Utah) -The lack of arms, the narrow body and the straight short legs – there seems to be an arc of white dots or something painted on top of this figure – some Barrier Canyon shamanic figures wear a crown of white dots.. Polly Schafsma [personal communication] says that throughout eastern Utah there are sometimes figures that are hard to place stylistically. She thinks that is because there was continuity between the Fremont and the earlier work or at least the earlier paintings influenced the Fremont.

Calendrical systems – this is always a guess--they could be. I was not there long enough to see if these markings interact with sunlight and shadow in any significant way. Heizer and Hester suggest that similar rock art drawings might represent diversion fences for game drives—but their examples had mountain sheep and shaman or bowmen.

Pictographs. Curvilinear style typified by presence of circles, concentric circles, circle chains, sun disks, curvilinear lines, mountain sheep and snakes and star figures. Curvilinear meander has a vague sort of composition in its tendency to fill an area defined by a single boulder.

Rectilinear style, textile-like fret designs, handprints, outline of a foot, etc.

After 1250 A.D. the Fremont began to disappear in the uneven fashion they appeared and by 1350 practically all of the Fremont population had abandoned the Great

Basin and Colorado Plateau provinces. Climatic conditions favorable to farming seem to have changed about this time forcing groups to rely more on wild food resources. Migration into to the area of Ute, Paiute and Shoshone populations may have displaced them. Different art styles suggest that they were pushed out or died out. The reasons for this total replacement of Fremont artifact types and total disappearance of Fremont patterns over its entire geographic range has not been determined.

http://www.staa.org

REFERENCES

Aikens, C. Melvin and David B. Madsen

1986 Prehistory of the Eastern Area. In, W. D’Azevedo (ed), HANDBOOK OF NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS, VOLUME 11, GREAT BASIN, pp. 149-160.

Madsen, David B.

1989 EXPLORING THE FREMONT. Utah Museum of Natural History, University of Utah.

Marwitt, John P.

1986 Fremont Cultures. In, W.S’Azevedo (ed), HANDBOOK OF NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS, VOLUME 11, GREAT BASIN, pp. 161-172.

Schaafsma, Polly

1990 INDIAN ROCK ART OF THE SOUTHWEST. School of American Research, Santa Fe. University of New Mexico press, Albuquerque

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

©2004 Southern Texas Archaeological Association, & Ellen Sue Turner

**************************************

The Ancient Treasure Of Range Creek

A Utah Rancher Reveals, and Turns Over, His Priceless Discovery to the Public

By T.R. Reid

Washington Post Staff Writer

RANGE CREEK CANYON, Utah, June 30 -- Seven centuries before Columbus went to sea, an American woman wove an elegant basket of grass and willow for her stone-walled house in this majestic canyon. In the early 1940s, a young cowboy named Waldo Wilcox found the basket, and the stone walls, in nearly perfect condition. "And I thought, this stuff has got to be protected," Wilcox recalled Wednesday.

For six decades, Wilcox and his family kept tight control over public access to a 12-mile stretch of Range Creek that had been the site of a bustling Fremont tribe community in the first millennium A.D. Few knew of its existence and Wilcox closely controlled the archaeologists and researchers he did permit to visit.

But now the aging rancher has turned over his 4,000-acre spread to the government -- and handed public land managers a significant dilemma along with it.

"A piece of ancient America like this, that has not been looted or vandalized, is almost unique -- an absolute treasure of our national history," said Kevin Jones, the Utah state archaeologist. "So the stupidest thing we could do is just open the gate.

"But this is public land now, and we owe it to the American public to let them see this fantastic collection of historic sites, so they can appreciate it and learn from it. The problem is how to balance public access with preservation."

On Wednesday, Wilcox, with the state and federal officials who now manage the site, offered the first public tour of the Wilcox Ranch ruins to a group of reporters. It is a string of 1,000-year-old villages so pristine that the ancient neighborhoods, cemeteries and granaries are still covered with beads and tools and pottery abandoned when the Fremont people left the canyon about 800 years ago.

"I don't think I've ever seen or heard of a collection of artifact scatters like we find here," said Shelley Smith, an archaeologist with the federal Bureau of Land Management. "My head gets all banged up when I'm in this canyon because every step I take my head is down and I'm finding ancient tools, just lying there."

As she said those words, Smith bent over and picked up a hand-chipped piece of red chert that had been cut to a sharp point. "That's a pretty nice awl somebody made a thousand years ago or so," she said. "That point was for sewing pieces of leather."

The Range Creek community, in Utah's high-desert Book Cliffs region about 130 miles southeast of Salt Lake City, was not as advanced as the famous cliff dwellings south of here at Mesa Verde, Colo., or Chaco Canyon, N.M. But the site is richer in many ways for archaeologists because its unsullied state teaches significant lessons about Fremont daily life.

In a rugged, wind-swept valley laced with the perfume of juniper and sage, the ancient Indians proved to be extremely efficient farmers and hunters, historians say. "They managed to provide for maybe 200, 250 people along this creek," Jones noted. "In modern times, the same stretch of land hasn't ever supported more than three families."

The Fremont built homes of round stone with pine bough roofs that were cool in the summer and warm and dry all winter. They carved and painted intricate designs on the towering cliff walls, sometimes erecting adobe awnings to protect their artwork from the elements. They built stone silos for corn and beans on the same high cliffs, presumably to protect their food supply from raiders.

Other ancient Indian villages in the Southwest have been ravaged by tourists, collectors and sometimes outright vandals over the centuries.

"Some of the Fremont people lived north of here in Nine Mile Canyon at about the same time of these Range Creek settlements," said Steven Burge, a Carbon County commissioner. "But we just don't have anything like the tools and artifacts up there we have found here. Up there, all the good stuff was hauled away to somebody's basement a long time ago. They're selling arrowheads on eBay."

Two factors preserved the community here. For one, the tall, narrow canyon -- studded with so many dramatic rock formations and natural arches that it would be a national park in many countries -- is difficult to traverse, which limited traffic until the rugged dirt road along the creek was built in 1947. Then, four years later, the Wilcox family erected gates at the north and south ends of the canyon, partly to keep their cattle from straying, but largely to keep out strangers.

"I was cussed all my life for locking those gates," the 74-year-old Wilcox said Wednesday. "Now the archaeologists tell me we were heroes for doing that. Otherwise the hippies would have come in here and destroyed the place."

Wearing a huge silver W on his belt buckle and the family cattle brand -- the Walking X -- on his pearl-buttoned shirt, the leather-faced rancher proudly pointed out ancient Fremont graves and the colorful cliff paintings he had discovered while herding cattle decades earlier. "I think the public should see this. I just don't want them digging it up and knocking things down."

Wilcox said he finally agreed to sell the ranch when he turned 70 and realized that he couldn't manage the work anymore. He now lives in what he calls "the big city" -- Green River, population 4,000 -- but clearly has second thoughts about leaving this canyon. "I made a deal and I'm stuck with it now, right or wrong," Wilcox said, his eyes rising wistfully to a stone arch on the clifftop that was named half a century ago for his father, Budge.

The ranch was purchased for $2.5 million by the Trust for Public Land, which held it until the state of Utah and the federal government appropriated the money to buy the 4,208-acre property. State and federal officials are now working together on a management plan that will protect the site's inestimable archaeological value and allow public visits at the same time.

"The public owns this site now," said Jones, the state archaeologist. "I wouldn't want to lock it up just for a few scientists."

But Wilcox is worried. "If you don't lock it up the way our family did," he grumbled, "the looters are going to come in here and destroy it."

http://www.washingtonpost.com

******************************************

The Fremont

By David Madsen

The prehistoric societies of the western Colorado Plateau and the eastern Great Basin can be characterized by variation and diversity; they are neither readily defined nor easily encapsulated within a single description.

Some people were primarily settled farmers, growing corn, beans, and squash in small plots along streams at the base of mountain ranges; some were nomads, collecting wild plants and animals to support themselves; still others would shift between these lifestyles. In some areas the population was relatively dense; in other places only small groups were found widely scattered across the landscape. People living in this region may even have spoken different languages or had widely divergent dialects.

Yet, despite the diversity of these lifestyles and the varied geography which helped structure their actions, these people seem to have shared patterns of behavior and ways of living that tie them together.

Today we call these scattered groups of hunters and farmers the Fremont, but that name may be more reflective of our own need to categorize things than it is a reflection of how closely related these people were to each other. "Fremont" is really a generic label for a people who, like the land in which they lived, are not easily described or classified. The Fremont culture was first defined in 1931 by Noel Morss, a young Harvard anthropology student working along the Fremont River in south-central Utah.

Because the Fremont are not easily categorized and do not readily fit into archaeological classification schemes, they have been a source of confusion and debate among archaeologists since they were first identified in the late 1920s. The differences between the many small bands of the Great Basin and those of the northern Colorado Plateau areas of the Intermountain West were often quite great. As a result, archaeologists have had a difficult time defining just who these people were and how they were related to each other. There are actually few artifact similarities among these groups. While the similarities include such things as a particular way of making baskets, a unique moccasin style, clay figurines, and gray pottery, the problem of categorizing Fremont groups is compounded by a number of factors. The figurines are quite rare, for example, and the baskets and moccasins are perishable materials which do not survive in most archaeological sites. There is, in fact, only one single non-perishable trait which ties these people together--a thin-walled gray pottery whose many variations have been found as far west as Ely and Elko, Nevada, in the central Great Basin, as far north as Pocatello, Idaho, on the Snake River Plain, as far east as Grand Junction, Colorado, at the foot of the western Rocky Mountains, and as far south as Moab and St. George, Utah, along the Colorado and Virgin rivers, respectively.

Most archaeologists believe the Fremont developed out of existing groups of hunter-gatherers on the Colorado Plateau and in the eastern Great Basin. These small groups were, like their Fremont descendants, diverse, flexible, and adaptable. They ranged from fairly large and relatively sedentary populations in environments where resources were more readily accessible, to small, highly mobile family-sized groups where resources were widely dispersed. Over a span of about a thousand years, from sometime after 2,500 years ago to about 1,500 years ago, different groups of these hunter-gatherers gradually adopted, in a piecemeal fashion, many of the traits associated with the farming societies of the Southwest and Mexico.

First, corn and other cultivated plants (called domesticates), initially developed in what is now Mexico, then diffused northward throughout the greater Southwest and were added to the wild food subsistence base of native people sometime about 2,500 to 2,000 years ago in areas on either side of the southern Wasatch Plateau. This early use of corn and other domesticates occurred well before settled villages developed, and it seems that farming at first was just a part-time affair practiced by people who were still essentially nomadic hunters and gatherers. The earliest "Fremont" corn, radiocarbon dated to 2,340-l,940 years ago, comes from a cache near Elsinore, Utah; corn in sites along Muddy Creek in the San Rafael Swell date to just after the time of Christ. These sites suggest that farming was well established in some areas by 2,000 years ago. Outside this region, however, full-time hunting and gathering lifestyles seem to have continued unchanged. For example, in the deserts of the eastern Great Basin, at all of the many cave sites like Fish Springs, Lakeside, Black Rock, and Danger Cave, domesticates are absent throughout this early period and subsistence was based entirely on wild foods.

Second, between about 2,000 to 1,500 years ago, many of the objects associated with the use of domesticates, such as pottery and large basin-shaped grinding implements, were added to the people's tools. It is noteworthy that Fremont pottery first occurs as early as 1,500 years ago in several caves and rock shelters associated with mobile hunting and gathering groups and is not found in what we think of as settled villages until several hundred years later. The production and use of these tools, in addition to the growing of corn, beans, and squash, appears to have spread to other hunting and gathering groups to the north as well as to both the east and west of the central Wasatch Plateau region. By about 1,300 years ago, sites with corn and pottery are also found in the Uinta Basin and around the Great Salt Lake; and within several hundred years after that, corn and/or pottery are present throughout the Fremont region.

Third, between about 1,750 and 1,250 years ago, architecture at some (but far from all) open sites changed from small, thin-walled habitation structures and subterranean storage pits to larger semi-subterranean timber and mud houses and above-ground mud- or rock-walled granaries. The presence of such substantial buildings suggests that, at some sites at least, some people were becoming more fully sedentary and were relying more on farming than on the collecting of wild foods.

By about A.D. 750 , hunting and gathering groups on the east and west sides of the Wasatch Plateau had adopted and modified many features of settled village life and to a greater or lesser extent had integrated them into their subsistence and settlement patterns. For the next five hundred years or so, this crystallized Fremont pattern remained essentially unchanged in the heartland of the Fremont region, but many of its features, such as its pottery, spread to groups as far away as central Nevada, southern Idaho, northwestern Colorado, and southwestern Wyoming. Whether these items were present in all these areas as the result of trade or local manufacture is presently unclear.

Significantly, there are actually very few common traits that distinguish what can be considered "classic" Fremont. Pithouse villages and farming are found over large areas of the United States about this same time and are not very helpful in distinguishing the Fremont from other groups. Many artifact forms, such as projectile point styles, also are not unique to the Fremont and are not helpful in separating the Fremont from their contemporaries. A number of other material items--such as stone balls, basin-shaped metates with small secondary grinding surfaces, and elongated corner-notched arrow points--are characteristic of the Fremont, but they are either so variable from place to place, or so limited in distribution, that they are not very useful traits for distinguishing the Fremont.

Fortunately, there are four relatively distinctive artifact categories which do distinguish the Fremont, materially, from other prehistoric societies. Unfortunately, they are only rarely found together. The first is a one-rod-and-bundle basketry construction style so unique that it has led some to suggest that the Fremont culture can be defined on the basis of this single artifact category alone. This technique is markedly different from that used by both contemporary Anasazi groups and from later historically known Numic-speaking groups such as the Ute and Shoshoni.

A second trait is a unique "Fremont" moccasin style constructed from the hock of a deer or mountain sheep leg. This and other moccasin types found in Fremont sites are very different from the woven yucca sandals of the Anasazi. A third item is actually an art style represented in three dimensions by trapezoidal-shaped clay figurines with readily identified hair "bobs" and necklaces. These same trapezoidal figures are depicted in Fremont pictographs and petroglyph panels. Magic and/or religious functions have been ascribed to these painted and sculpted figures, but no one really knows their purpose or meaning.

The fourth and last major artifact category is the gray, coil pottery which is most often used to identify archaeological sites as Fremont. This pottery is not very different from that made by other Southwestern groups, nor are its vessel forms and designs distinct. What distinguishes Fremont pottery from other ceramic types is the material from which it is constructed. Variations in temper, the granular rock or sand added to wet clay to insure even drying and to prevent cracking, have been used to identify five major Fremont ceramic types. They include Snake Valley gray in the southwestern part of the Fremont region, Sevier gray in the central area, Great Salt Lake gray in the northwestern area, and Uinta and Emery gray in the northeast and southwestern regions. Sevier, Snake Valley, and Emery gray also occur in painted varieties. A unique and beautiful painted bowl form, Ivie Creek black-on-white, is found along either side of the southern Wasatch Plateau. In addition to these five major types found at Fremont villages, a variety of locally made pottery wares are found on the fringes of the Fremont region in areas occupied by people who seem to have been principally hunters and gatherers rather than farmers.

At the height of this classic Fremont period, about 1,000 years ago, people who in one way or another fit the rather broad description of Fremont could be found from what is now Grand Junction, Colorado, on the east to Ely, Nevada, on the west. They lived as far north as modern Pocatello, Idaho, and on the south to present-day Cedar City, Utah.

After about A.D. 1250, the Fremont as an identifiable archaeological phenomenon began to disappear in much the same uneven fashion that it appeared. That is, between the years 1250 and 1500, classic traits such as one-rod-and-bundle basketry, thin-walled gray pottery, and clay figurines disappear from the Fremont region. No one can quite agree on what happened, but there seem to be a number of interrelated factors behind this change. Two seem most likely. First, climatic conditions favorable for farming seem to have changed during this period, forcing local groups to rely more and more on wild food resources and to adopt the increased mobility necessitated in collecting wild food. By itself, however, this climatic change probably would not have resulted in the Fremont demise, because the flexibility and adaptability which characterized the Fremont had allowed them to weather similar changes. However, new groups of hunter-gatherers appear to have migrated into the Fremont area from the southwestern Great Basin sometime after about 1,000 years ago. These full-time hunter-gatherers were apparently the ancestors of the Numic-speaking Ute, Paiute, and Shoshoni peoples who inhabited the region at historic contact, and perhaps they displaced or replaced the part-time Fremont hunter-gatherers with whom they were in competition.

Whether or not Fremont peoples died out, were forced to move, or were integrated into Numic-speaking groups is unclear, and even the matter of the postulated Ute/Paiute/Shoshoni migration remains a matter of spirited debate. It appears that the sudden replacement of classic Fremont artifacts by different kinds of basketry, pottery, and art styles historically associated with Utah's contemporary native inhabitants suggests that Fremont peoples were, for the most part, pushed out of the region and were replaced rather than integrated into Numic-speaking groups. This interpretation is strengthened by the fact that the most recent Fremont or Fremont-like materials, dating to about 500 years ago, are found at the northern and easternmost fringes of the Fremont region, in the Douglas Creek area of northwestern Colorado and on the Snake River plain of southern Idaho--areas at maximum distance along the postulated migration route of Numic-speaking populations.

David B. Madsen

Article is from the UTAH HISTORY ENCYCLOPEDIA. Powell, Alan Kent,

ed. Salt Lake City, Utah : The University of Utah Press, 1994

- See: David B. Madsen, Exploring The Fremont (1989).

http://www.kued.org

Comments (0)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

HiddenMysteries

Main Headlines Page

Main Article Page

Secrets of the Lost Canyon

http://www.hiddenmysteries.net/newz/article.php/20061227133808109

Check out these other Fine TGS sites

HiddenMysteries.com

HiddenMysteries.net

HiddenMysteries.org

RadioFreeTexas.org

TexasNationalPress.com

TGSPublishing.com

ReptilianAgenda.com

NationofTexas.com

Texas Nationalist Movement