|

HiddenMysteries.com HiddenMysteries.net HiddenMysteries.org |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

Beyond the alphabet

Saturday, June 02 2007 @ 03:31 AM CDT

Increase font Decrease font

This option not available all articles

There is white, there is black, and then there is Rasheed Quraishi, writes Rania Khallaf

What could unite Arabs, spiritually, more than the calligraphic tradition? Well, the Algeria-born Rasheed Quraishi brought a magnificent example of its contemporary application to downtown Cairo last week.

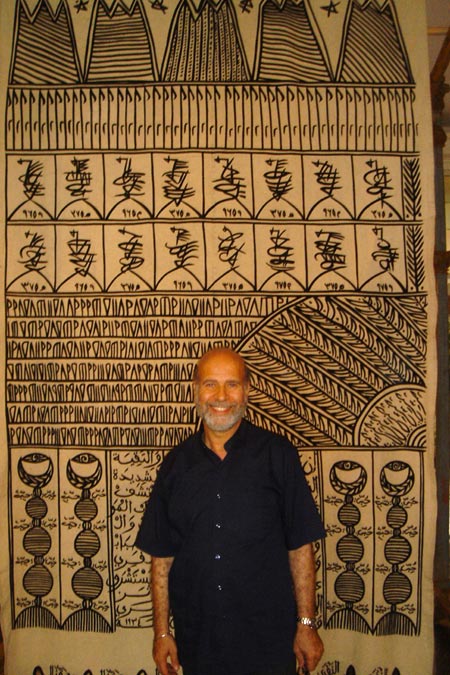

His work, which has been acquired by some of the world's most significant museums, including the British Museum, the Johnson Herbert Museum in New York, the Mankind Museum in London, and the Modern Art Museum in Cairo. Coming from a long line of Sufis, Quraishi seems to inject spiritual energy into his work, and takes calligraphy far beyond its principal function of beautifully inscribing words. His project in Cairo, facilitated by the French Cultural Centre (FCC) -- Quraishi chose the city for the khayamiya (tent making) tradition of Old Cairo, a 1,000-year-old practise passed from one generation to the next -- is undertaken in collaboration with a number of its most skilful artisans. In an FCC seminar, he explained that the project revolves around the number seven, inspired by its many spiritual-symbolic derivations.

Seven is a very distinguished number that enjoys a position of prominence in all three monotheistic traditions, after all. And Quraishi's principal work in Cairo is a single seven made up of 99 pieces (reflecting the 99 names of God), to be produced on a scale of 3.30 m by 2.10 m in collaboration with the artisans in question. Designed by Quraishi and produced in white khayamiya and black cotton, it is meant to symbolise the life and work of exactly 14 prominent Sufis to whom the artist relates. Seven pieces will be dedicated to each, with the 99th piece depicting the names of God. Launched in 2006, the project should be on show in one of Old Cairo's many historical buildings next year. Of the 99 pieces, no less than 40 have already been completed now. Two of them, proudly exhibited at the FCC main hall, prove exceptionally beautiful, their shape and ornament reflecting the life work of Sufi masters who contributed much to the history of civilisation. One can only begin to imagine what the completed work will look like, or the depth its effect will have on the spiritually aware.

"I feel very happy to be here in Egypt," the Paris-based French- Algerian said. "I first came 25 years ago; I came another time eight years ago. Now I am here to present work." He arrived directly from Damascus, he explains, where he undertook a similar project. And his time in Damascus was inspired by a peculiar event. He was working steps away from the tomb of Abdel-Qader Al-Jaza'iri in Paris when a puppy accompanied by an old lady urinated in the vicinity, a desecration that made Quraishi furious. It was then that he decided to build a shrine in tribute to the master; he recalled the incident while in Syria, where some 350,000 followers of Al-Jaza'iri live. Speaking in French with the occasional Arabic interjection, the painter-designer-writer-calligrapher was extremely engaging: "Every project I start is conceived in relation to a specific environment, a people and a history. Damascus was somewhat different as the idea was rather more concerned with the ancestral history of Sufi masters: to produce, for each Sufi order, a silk banner; and each banner has three different colours." Here as elsewhere the project has been "nomadic", touring the world.

"This is why I have huge storerooms in which to keep my work," Quraishi explains. "When they've run their course of exhibitions, I donate them to the most important museums in the world." Partly financed by the FCC, in the Cairo project Quraishi is paying the artisans out of his own pockets. Though surprising in itself, it is something that fits in with Quraishi's mentality as a whole; and he is particularly impressed with the tradition in question. "As old as ancient Egyptian mummification," he says. "They used to paint adornments on the cloth used to cover the mummies." That, indeed, was part of his inspiration: "I chose Cairo because so many Sufi scholars went through Egypt, too, of course. It's a project that reflects the history of humanity in general, expressing the dimensions of Sufism as a universal trend." Equally universal, he pointed out, sadly, is the dearth of skilled artisans and the fact that authentic products like khayamiya do not draw in the average consumer. "Yet it's the responsibility of the artisans to develop their crafts, to make them more popular and marketable. It's a craft that, seeping out of Egypt, was known in many African countries for many thousands of years. We cannot simply let it die out now." The word itself, as novelist Gamal El-Ghitani has pointed out, is a special word: "Derived from the Arabic word khaymah (tent) and being a reference to its fabric... it symbolises marriage and death, war and peace, combining two contradictory and states of existence."

Nor does Quraishi see himself as primarily a calligrapher: "Arabic calligraphy requires a high degree of proficiency that I do not have. I've often sought the assistance of professionals." For El-Ghitani, however, the project "is a unique vision, creatively distinct". On one side of the Sidi Tijani piece, for example, the text reads as Arabic; on the other side, it reduces to symbols. Egypt is the perfect place for such a project," because, he says, "writing originated in this land as a sacred act; and it remains sacred in the collective, popular faith to this people to this day. In Upper Egypt, to cure sickness, a sheikh or an imam is asked to write a few lines on a piece of paper, which, sanctified, is then believed to remove the disease." Writing, like Sufism, becomes meaningful and symbolic-ornamental by turns: "It is a current; it keeps coming and going." Egypt, it is worth adding, has been famed for its textile industry since long before the advent of Islam, when qabaty (Coptic) fabric was sought after in the Arabian peninsula. For centuries the cover of the holy Kaaba was made in Egypt -- a tradition that survived until foundation of the modern Saudi state and the discovery of oil there.

http://weekly.ahram.org.eg

Rasheed Quraishi

Comments (0)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

HiddenMysteries

Main Headlines Page

Main Article Page

Beyond the alphabet

http://www.hiddenmysteries.net/newz/article.php/20070602033158971

Check out these other Fine TGS sites

HiddenMysteries.com

HiddenMysteries.net

HiddenMysteries.org

RadioFreeTexas.org

TexasNationalPress.com

TGSPublishing.com

ReptilianAgenda.com

NationofTexas.com

Texas Nationalist Movement