|

HiddenMysteries.com HiddenMysteries.net HiddenMysteries.org |

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

Defending Byzantium

Friday, November 21 2008 @ 05:41 PM CST

Increase font Decrease font

This option not available all articles

Sometimes deprecated and often misunderstood, Byzantine civilisation is the subject of this winter's major exhibition at London's Royal Academy, writes David Tresilian

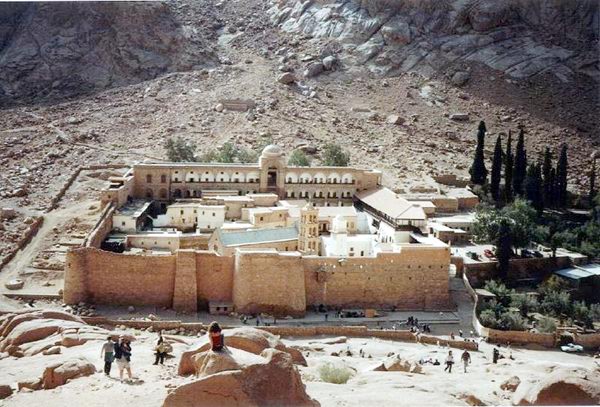

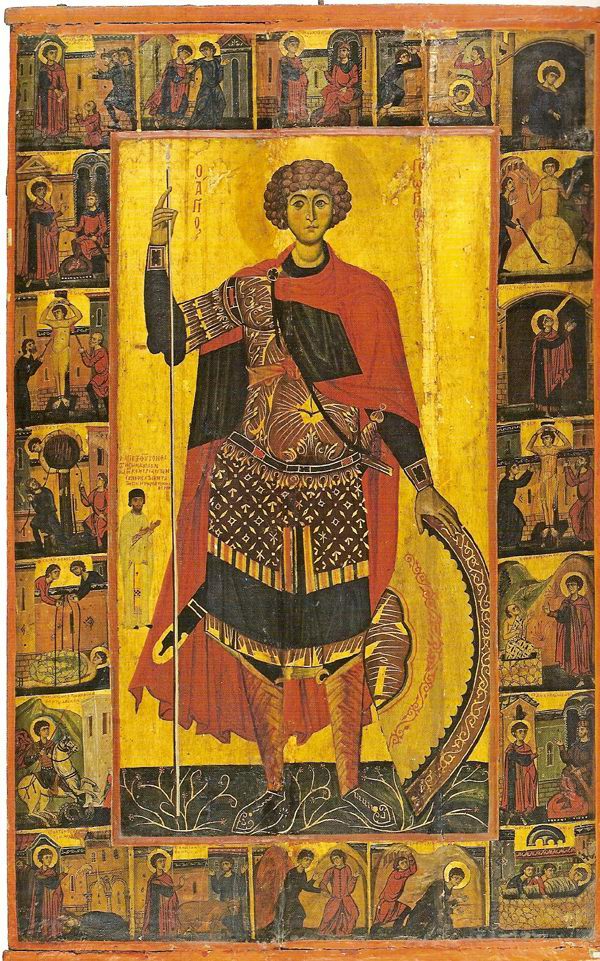

St Catherine's Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai, founded by the Byzantine emperor Justinian in the 6th century CE (top); Thirteenth-century icon of St George from St Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai. Promised for the London Royal Academy exhibition, this group of icons did not in fact arrive

********************************************

Lasting some 11 centuries from the foundation of the city of Constantinople, today's Istanbul, on the site of the Greek city of Byzantium by the Roman emperor Constantine in 330 CE to its final defeat at the hands of the Ottomans in 1453, at its height the Byzantine Empire took in the whole of the eastern Mediterranean and stretched from Anatolia and the Balkans to Egypt and north Africa. It always styled itself the heir of the Roman Empire and of classical civilisation as a whole.

Examples of Byzantine architecture can still be seen in Istanbul in the shape of the Hagia Sophia, the church of the holy wisdom, built by the emperor Justinian in the 6th century CE, and in the ruins of the Byzantine city walls. Memories of the empire are scattered across the Mediterranean, from the mosaics of the Byzantine emperors in the churches of the Italian coastal city of Ravenna to the traditions continued by the monks of St. Catherine's Monastery in the Egyptian Sinai.

However, Byzantium has sometimes suffered from a bad press, at least in western Europe, and this is summed up in views expressed by the 18th- century English historian Edward Gibbon in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. "In the revolution of ten centuries" of Byzantine history, Gibbon wrote, "not a single discovery was made to exalt the dignity or promote the happiness of mankind."

The Byzantines "held in their lifeless hands the riches of their fathers, without inheriting the spirit which had created and improved that sacred patrimony: they read, they praised, they compiled, but their languid souls seemed alike incapable of thought and action... Their understandings were bewildered in metaphysical controversy; in the belief of visions and miracles, they had lost all principles of moral evidence; and their taste was vitiated by the homilies of the monks."

Byzantine civilisation, Gibbon wrote, was the expression of vices that had been responsible for the fall of the western Roman empire: there was an absence of civic virtue among its citizens, he believed, and there were the enervating effects of what he called the "base and imperious superstition" of Christianity, adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire by the emperor Theodosius in 380 CE.

So ingrained have such views of Byzantine civilisation become that the organisers of Byzantium 330--1453, which opened at the Royal Academy in London late last month and runs until March next year, seem to have felt duty bound to combat them. This is a major exhibition, the largest of its kind to be held in Britain, and it has been organised in collaboration with the Benaki Museum in Athens and includes works lent by collections in Europe, the United States and the Middle East.

"Long regarded as an age of decadence, Late Antiquity has more recently become a fashionable subject, even a growth industry, among professional historians," writes one authority in the magnificent catalogue the Academy has produced to accompany the exhibition, without however noting that for Gibbon the rot really set in when Late Antiquity gave way to Byzantine civilisation proper, in which a central place was given to the theocratic role played by the emperor.

The period of Late Antiquity, the first part of Byzantium's history, lasted until the Arab conquests of the formerly Byzantine territories of Egypt and the Levant in the 7th century CE, and it saw the spread of Christianity throughout the eastern Mediterranean and the foundation of a sophisticated, urban civilisation that continued Roman traditions of government in a manner sharply contrasting with the collapse of the western empire.

From the 7th and 8th centuries on, the Byzantine Empire, having recovered from the Arab sieges of Constantinople in 674-678 and 717-718, slowly lost its Roman roots, Greek replacing Latin both as the empire's lingua franca and as the language of government and administration.

However, while there would perhaps have been little that was recognisably Roman about the culture that greeted the European crusaders when they looted Constantinople in 1204 CE, part of the fall- out from the Fourth Crusade, the Byzantines nevertheless considered themselves to be the heirs of Rome right up until the fall of their city to the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II in 1453 at a time when the empire had been reduced to little more than the city of Constantinople itself.

Indeed, it is this inheritance that is still expressed in Arabic: the Arabic word "rum" (Rome), used in the Qur'an in the context of Arab relations with Byzantium, denotes the Greek-speaking inhabitants of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire rather than the Latin remnants of the destroyed western empire.

With over a thousand years of Byzantine history to cover, the organisers of the Royal Academy exhibition have had to be selective. Entering the exhibition, splendidly laid out across ten rooms in the Academy's main exhibition galleries, the visitor is introduced to Constantine's foundation of Constantinople and to the civilisation of Late Antiquity that for a while at least linked the eastern with the western portion of the failing Roman Empire.

From here, the focus moves to Justinian, perhaps the greatest of the early Byzantine emperors, who ruled from 527 to 566 CE. During his long reign, Justinian embarked upon a building programme that saw the construction of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, as well as of St. Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai. The latter remains an Orthodox foundation to this day and one that is linked to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem rather than to the Egyptian Coptic Church.

However, Justinian's activities extended far beyond the religious sphere. It was during his reign and by his order that Roman law was codified, and he embarked upon military campaigns in both the west and the east that temporarily restored Italy and north Africa to Roman and Byzantine rule and secured the empire's eastern boundaries against attacks from Sassanid Persia. This glorious period in Byzantium's history is reflected in the present exhibition in the shape of mostly religious materials, including ivories, gold and silver vessels and illustrated manuscripts.

For Gibbon what distinguished the inhabitants of Byzantium from their ancestors who had lived during the earlier, classical periods of Greek and Roman civilisation was their taste for "metaphysical controversy," their "belief of visions and miracles," and their "taste... vitiated by the homilies of the monks." Writing in the exhibition catalogue, the historian Cyril Mango, professor of Greek and Byzantine literature at Oxford University, says that "it is a mistake to assume that for 100 years the Byzantine public did nothing but squabble over the veneration of icons," yet this exhibition goes a long way towards demonstrating just how important such controversy was in Byzantine life.

It was during Late Antiquity at the height of the eastern Roman Empire, for example, that the Byzantine emperors convened the various synods -- of Nicea, Constantinople and Chalcedon -- that defined the doctrine of the early Christian church, especially with regard to the sometimes vexed issue of Christology. The theology of the Trinity was worked out at the Council of Nicea in 325 CE, and at the Council of Chalcedon a little over a century later the relationship between the human and divine nature of Christ was clarified, though this was rejected at the time by the patriarch of Alexandria. As a result, the Egyptian Coptic Church, like the other eastern orthodox churches, still insists on Christ's single nature in a doctrine known as monophysiticism.

Perhaps these councils, and the controversies to which they gave rise, was what Gibbon had in mind when he wrote that the Byzantines spent too much time on "metaphysical controversy," though the solutions worked out at the time form the basis of subsequent Christian theology. However, more important from the visual point of view, and certainly for the visitor to the present exhibition, was the Byzantines' emphasis on religious images, or icons, and the settlement they arrived at to circumvent what was read as a biblical interdiction on their production.

Reached only after a century of near civil war had raged throughout the empire between those who supported the emperor Leo's ban on religious images, pronounced in 730 CE, and those who saw the devotional use of religious images as part and parcel of Byzantine religious orthodoxy, this settlement to the so-called iconoclastic controversy declared the production of icons legitimate, and the present exhibition contains some magnificent examples of Byzantine icons lent by institutions throughout Greece and eastern Europe. Many of these were produced using a technique called "micro-mosaic", which, as its name suggests, involves the painstaking application of tiny pieces of mosaic to produce a single image.

While the exhibition contains many such pieces, particularly in its eighth room which is dedicated to icons, it is a pity that the collection that many visitors will have come to see -- a group of icons lent to the exhibition by St. Catherine's Monastery -- are in fact not present and have been replaced by facsimiles. As a note at the exhibition explains, the St. Catherine's icons, though promised, did not in fact arrive. It is unclear whether it was the monks of St. Catherine's or the Egyptian authorities who were responsible for the delay.

While the organisers of Byzantium 330--1453 have included sections on Byzantine home life, in the shape of a room given over to domestic objects such as pottery, fragments of textiles and jewelry, and there is a room that aims, perhaps not entirely successfully, to give some idea of the magnificence of the Byzantine court, it is the religious aspect of Byzantine civilisation that takes pride of place in the exhibition throughout, as is perhaps only natural given the magnificent visual material available.

Anyone interested in the history of the eastern Mediterranean, of Christianity, or of relations between Byzantine, Arab and Ottoman Turkish civilisations can not fail to learn from visiting this exhibition.

Byzantium, 330--1453, Royal Academy, London, 25 October 2008--22 March 2009

ahram.org.eg

Comments (0)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A word from our sponsor

HiddenMysteries

Main Headlines Page

Main Article Page

Defending Byzantium

http://www.hiddenmysteries.net/newz/article.php/20081121174124937

Check out these other Fine TGS sites

HiddenMysteries.com

HiddenMysteries.net

HiddenMysteries.org

RadioFreeTexas.org

TexasNationalPress.com

TGSPublishing.com

ReptilianAgenda.com

NationofTexas.com

Texas Nationalist Movement