Alexander's lost tomb

Monday, May 21 2007 @ 01:20 PM CDT Views: 383

The epic exploits of Alexander the Great have been memorialised in fiction, films and biographies. His military genius and colourful personality, not to mention his unexplained death and multiple burials, have long held fascination.

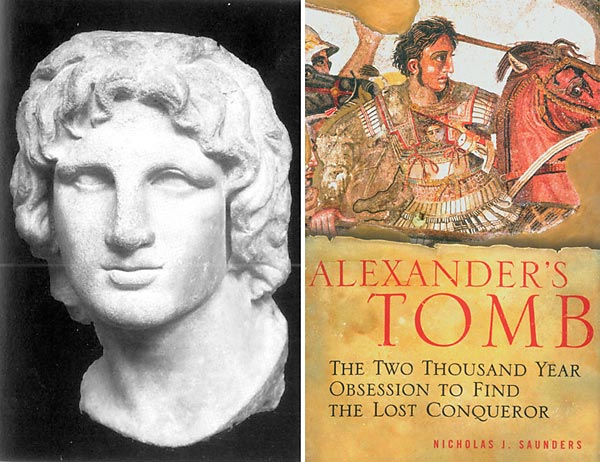

An idealised portrait of Alexander

There has been no end of speculation as to why his mortal remains were carried far and wide -- from Babylon where he died in 323 BC at the age of 32 and where his mummified body lay in state for two years; to its transportation to Macedonia, when it was hijacked en route by his trusted general Ptolemy and taken to Memphis, the sprawling city on the banks of the Nile. The body was subsequently transported to Alexandria where Ptolemy had built a grand mausoleum, the Soma, for Alexander's remains.

Nicholas Saunders, British archaeologist, social anthropologist and the author of Alexander's Tomb: The Two Thousand Year Obsession to Find the Lost Conqueror, has endeavoured to unlock one of the mysteries of the ancient world -- what happened to the body and where it was buried. He points out that the move from Memphis to Alexandria was "a pivotal moment in Egypt's 300-year transition from native Pharaonic grandeur to the advent of Roman rule", and points out that, despite a good deal of search and study, "we cannot be sure when it occurred or, in fact, who was responsible... The ancient writers are silent on exactly where Ptolemy finally buried Alexander and are vague about the funeral." In Chapter Four of his book, entitled "Who moved Alexander's Corpse", Saunders tries to untangle the thread of speculation.

"Ptolemy had the future of Alexander's body and tomb firmly in his sights from the beginning," writes the author. "He buried the king in Memphis (no doubt in an attempt to legitimise his position as Pharaoh of Egypt and sanctify his rule) with a vision of later moving the body to a grand tomb in Alexandria," and points out that while Alexander lay in Memphis, Ptolemy built the Soma for his remains so that, after the transference of the body, the deification of Alexander, the Macedonian conqueror, could be combined with Ptolemy's own. In other words, "by promoting himself as Alexander's heir, Ptolemy created a sacred genealogy linking himself to the ancient line of Egyptian Pharaohs with Alexander as the linchpin... Only when it was finally laid to rest in his eponymous city (i.e. Alexandria) amid cult and grandeur, could Ptolemy propel the living god on a journey into the future."

Ptolemy's invaluable ally in this whole design, writes Saunders, was the high-ranking Egyptian Priest Manetho "who schooled him in the bizarre cults and practices, and the confabulations of myth and history that fascinated Egypt's new Macedonian ruler".

The body of Alexander was an important and potent relic that drew thousands of visitors to the Mediterranean capital and seaport. Saunders writes that, "touring the body" was de rigeur for visiting royalty, diplomats, generals, scholars and the merely curious during the three centuries of Ptolemaic rule. "Disembarking from ships, dismounting from horses, or walking through the city's marbled streets, eager pilgrims were drawn to Alexander's tomb... All gazed on (it), though not on the mummy itself enclosed in its grotto, where the cool temperature helped preserve it."

The tomb remained an attraction even after the Roman conquest in 30 BC. Caesar himself set a precedent when he reputedly wept over how little he had achieved in comparison to Alexander, who had conquered the known world at the age of 32. Octavian was forthright in his desire to see Alexander's body itself, not just his tomb, and "he ordered the sarcophagus to be brought forth from its inner sanctum and after gazing on it, showed his respect by placing upon it a golden crown and strewing it with flowers."

The Temple of Amun in Siwa where he consulted the oracle

These two emperors blazed a path to Alexander's tomb that was trodden by Roman emperors who visited Egypt later, including Septimus Severus (193-211 AD) who, for some unknown reason, turned Alexander's tomb into a secret repository for books and manuals on magic and alchemy. Indeed, bitter conflict between rival Christian factions in the third century brought about the ruin and abandonment of large areas of Alexandria, but what subsequently happened to the tomb is not known because, Saunders says, "the ancient sources are silent." However, "by 298 [AD] Alexander's tomb had entered the realm of rumour and legend, half-truths, possible sightings, romance, and deception." The last mention of the grand mausoleum, Saunders adds, was made by John Chrysostom (340-407 AD), one of the most eloquent and influential of the early church philosophers, who launched a bitter attack on Alexander's tomb in a homily on St Paul's Epistle to the Corinthians. He asks a rhetorical question: "Tell me, where is the tomb of Alexander? Show me, tell me the day on which he died."

The truth will probably never be known. Not, that is to say, unless the body is found. And herein lies the widespread and ongoing interest in its discovery: it has long been an object of archaeological obsession, not for the treasures which were almost certainly looted long ago but for the body of Alexander himself. He was, after all, a demi- god, and after his death the Roman emperors promoted his divinity by visiting his tomb because they wanted to be associated with his greatness.

Conspiracy theories were rife in Greek and Roman times. Two traditions arose: one, that the death of the conqueror was natural, and the other that it was suspicious. Why the body itself was embalmed remains another mystery, since it broke with royal Macedonian tradition. Andrew Stewart, author of Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Policies, provides an interesting translation of an ancient text: "Alexander's embalmed body was lifted into a golden coffin lined with scented herbs. Perdiccas [guardian of Alexander's heirs], according to one account, placed Alexander's body in the casket, covered it with a robe and purple cloak, and tied the royal diadem across his forehead. The body was anointed with perfumes mixed with honey, and the sarcophagus was draped with a purple cover."

Saunders travelled for decades, carrying out research and taking notes in Greece, Turkey, and Egypt, but his journeys only served to raise new questions and strengthen his interest in this towering historical figure. "For over twenty years," he writes, "the idea of Alexander the Great's tomb has been a fascination. It was less an interest in discovering the tomb or its site, than of searching for its traces in the world, tracking its influence on history, and charting the lives and times of the various characters and personalities who have been associated with it."

Alexander's Tomb brings together thousands of years of conjecture, combining a detailed chronological account of the history of the tomb with the first publication of new discoveries. Using maps and discussions of where the walls of Alexandria stood, and how they changed, Saunders lays out the most likely possibilities.

New research is now revealing hitherto unrecognised evidence, and there is excitement in some academic circles. Andrew Chugg, author of The Lost tomb of Alexander the Great, has written a magnanimous review of Saunders's book, crediting the author with breaking the facts about Alexander's death and early tomb locations and commenting that the illustrations were well presented, relevant and useful, and that most had not been seen elsewhere. Chugg did say, however, that he had approached the book with a slight "worry" at the author's claim, "be it all in a small chapter of the book", that the body of Alexander was in Venice.

Saunders refers to the much-publicised claim made by the Greek archaeologist Liana Souvaltzi in 1995 to the effect that she had discovered Alexander's tomb in Siwa Oasis. Souvaltzi announced that three limestone tablets were inscribed with the tale of Alexander's poisoning and how Ptolemy had taken his body to the oasis for burial. She went public with the discovery, but her lectures were not well received. Saunders describes in detail the growing furore that followed a visit to Siwa by representatives of the "Antiquities Association" and a group of experts who at first confirmed her discovery as "unique" and "really Macedonian". She also describes a subsequent visit by Greek delegates from the minister of culture in Athens who were "unconvinced"; and, finally, the "flurry of activity and acrimonious edge (that) unsettled the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, which quickly convened a second press conference distancing themselves from this embarrassing media circus." It amounts to a fascinating chapter about the gradual crumbling of Souvaltzi's credibility, the questioning of her professionalism, and the final exploding of her hypothesis when the Greek inscriptions were translated by specialists.

Alexander's tomb is as powerful an idea, as it ever was as a physical place, Saunders says. "It has been a lodestone for the world of classical paganism, Christianity, and Islam, and a sorcerer's stone for history, archaeology, and the tortured politics of the modern world. Alexander's life was short, but the aftermath of his death -- some three hundred years before Christ -- is surely the longest post-mortem affair in human history. The search for the tomb is an epic tale whose final chapter remains unwritten."

Indeed, the disappearance and fate of the tomb of Alexander is among the most momentous and tantalising of all the mysteries we have inherited from the ancient world. There has been a never-ending quest for his final resting place. Generations of archaeologists and historians have succumbed to the allure, yet have so far failed to find convincing answers. In recent years conspiracy theories have given way to an equal number of scientific explanations. New research is revealing hitherto unrecognised evidence and providing some fresh insights into the burial and disappearance of the body of Alexander, which is creating renewed excitement in some academic circles.

In a review of Saunders's book, Bob Brier, senior research fellow at Long Island University, wrote: "There is no shortage of potential sites for the lost tomb. The most notorious is, of course, the sarcophagus in the British Museum that Napoleon's savants believed was Alexander's. Later, when hieroglyphs were deciphered, it was revealed that the sarcophagus was carved for Nectanebo II, the last native ruler of Egypt. So it's not Alexander's. Or is it? Nectanebo fled Egypt and never used it, so it is possible that Ptolemy buried Alexander in the vacant royal sarcophagus. There was even a faint rumour that Nectanebo was Alexander's father."

Saunders, who studied archaeology and social anthropology in the United Kingdom and who has taught and written numerous books on these topics, offers in Alexander's Tomb the epic tale of the ongoing quest to unlock this great mystery of the ancient world. He is less interested in discovering the site of the tomb than in searching for its traces in the world, tracking its influence on history, and charting the lives and times of the various characters and personalities who have been associated with it for 2,000 years. This is an important book, well written, and fascinating in its content.

When Saunders's book was published, Publisher's Weekly carried a tantalising review, lauding him for deftly chronicling the various searches for Alexander's tomb from antiquity to the present, and adding that the author's "lively prose drew readers into this compelling tale of conquest, political intrigue and the aura surrounding one of history's great heroes". This alone would ensure an enthusiastic general readership, but now that the book has also been reviewed in "Editor's Pick" in Archaeology Magazine, sales can also be expected to rocket among Egyptology enthusiasts.

Reviewed by Jill Kamil

A RECONSTRUCTION of the hearse which was conveying Alexander's body to Aegae to rest with his ancestors in Macedonia in the autumn of 321 BC, by Candace Smith. According to a contemporary historian, it was designed as a temple, its Ionic columns adorned with golden acanthus tendrils, and on each of the four corners a Nike victory statue. A golden olive wreath on a stylised palm stood on the top of a barrel roof fashioned from golden scales, and two golden lions guarded the entrance to the interior, where the mummified Alexander lay in his gold sarcophagus. The hearse here depicted was hijacked by Ptolemy and taken to Memphis.

Saunders, Nicholas J (2006) Alexander's Tomb: The Two Thousand Year Obsession to Find the Lost Conqueror, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo

Story Options